1. Introduction

High Speed Sync lets you flash at high shutter speeds. Find out if you've got it and how it can improve your shots.

Some participants on my recent Costa Rica and Falkland Islands workshops noticed a problem when they turned on their flashes to add fill light. We were photographing birds with long lenses and Better Beamer Flash Extenders, and were shooting wide open (e.g. f/4 or f/5.6) to maximize shutter speed, minimize motion blur, and soften the background. Typical settings at ISO 200 in full sun were around 1/2,000 sec at f/5.6.

Gentoo Penguin and chick, Falkland Islands

EOS 1D Mark II, ISO 100, 500 mm lens, 1/700 sec @ f/8, fill flash @ -1.7 with Better Beamer Flash Extender and Speedlite 580EX in High Speed Sync mode. Fill flash softens the shadows the parent casts on this tiny chick.

When participants turned on their flashes for fill light, the result for some was very overexposed shots. (Thanks to digital, the blown out shots were immediately obvious.) But what was causing this problem, and how could we fix it?

Maximum sync speed

What we experienced is an object lesson in the significance of a camera's maximum flash sync speed (sometimes referred to as simply "sync speed"). Most photographers know that better cameras have higher maximum sync (synchronization) speeds, but the value of this feature isn't always obvious.

A camera's maximum sync speed is the fastest shutter speed at which you can use a "standard" flash. (I say "standard" because some systems now offer a "high speed sync" mode that allows you to use flash at any shutter speed. More about that key innovation below.)

A standard hotshoe flash gives out a very short pulse of light. The flash duration can vary from around 1/1,000 second to 1/50,000 sec or shorter. The less light that's needed, the shorter the duration; that's how TTL flashes reduce their light output below full power.

Maximum sync speeds range from as low as 1/60 sec on entry-level SLRs to 1/250 or even 1/500 sec on top-of-the-line models. Why is there a limit? It comes from the way SLR shutters work. The focal plane shutter on your SLR consists of two curtains which work in tandem and move up and down across the frame to expose it to light for the required amount of time (shutter speed).

For a long exposure, say 1 second, the first curtain quickly opens to expose the film or sensor. After 1 second has elapsed, the other curtain quickly closes to end the exposure. And that's the way it works, until you exceed the maximum sync speed.

2. Camera Designers Employ a Neat Trick

At speeds above the maximum sync, the curtains can't move fast enough to fully open and then quickly close. So camera designers employ a neat trick: At high shutter speeds, the second curtain begins to close before the first curtain fully opens. In this way, a band or slit of exposure moves across the frame, which effectively yields a short shutter speed.

The flash duration in standard mode is usually much shorter than the time it takes for the shutter to travel across the frame—the flash is effectively instantaneous. But at any given instant at very high shutter speeds, only a part of the frame is exposed by this moving slit. That's why you can't use your standard flash at speeds higher than the sync speed: part of the frame would be covered by the partially opened curtains and would be black.

How cameras handle maximum sync speed

Most cameras automatically reduce the shutter speed down to the maximum sync speed if you had set it higher and then turned on the flash. Some may display a warning but not prevent you from taking a flash shot at speeds higher than the maximum sync speed. If you take a shot anyway you'll see part of your frame goes black (if flash is your only light).

Why sync speed matters

Now you can see why photographers crave high maximum sync speeds. In Costa Rica and the Falklands we were happily shooting at 1/2,000 sec at f/5.6 without flash. That's a comfortable shutter speed for big telephotos and active subjects. But once the flash was turned on in standard mode, our shutter speeds were automatically reduced, in this case by several stops. For my Canon EOS 1D Mark II, that means a shutter speed of 1/250 sec (maximum sync speed for that body).

To keep the same exposure, I'd have to change my aperture to f/16, but with some unwanted side effects.

With a shutter speed of 1/250, I'd have to stop down to f/16 to maintain the same ambient exposure. The extra depth of field would sharpen my background, which I prefer to keep soft. And the slower shutter speed could cause problems with subject motion or camera shake at my 500+ mm focal lengths.

Furthermore, in Aperture Priority mode, the aperture is fixed until I change it. If I didn't notice the blinking exposure display (easy to miss in the heat of battle), I'd be shooting at 1/250 sec and f/5.6—and overexposing the ambient light by 3 stops!

The problem is solved

That explained the gross overexposures some people were suddenly seeing. Aperture Priority mode is a typical way to capture wildlife with long lenses. Turning on the flash forced the shutter speed down, but the aperture dutifully remained where we'd set it.

Some people suspected that their flashes weren't set correctly or were malfunctioning and putting out way too much light, causing the overexposure, but that wasn't the case. (When you've been waiting for an hour until a penguin has returned from the sea and is actively feeding its chick, you often don't notice blinking warnings in the viewfinder.) Change your f/stop to one that's compatible with the flash sync speed, and the overexposures problem is solved.

Of course, that solution requires a big compromise: To get the benefits of fill flash, you're forced to use a slow shutter speed and high f/stop—just the opposite of what you'll usually want with long lenses and active subjects. Maybe we should just turn the fill flash off ...

3. A Better Solution

Many cameras can now use flash at their highest shutter speeds.

But you may have another option. In fact, I've found that many photographers have this feature, but aren't aware of it. Many cameras can now shoot with certain flashes at any shutter speed, effectively getting around the old limitation of maximum sync speed. Canon calls this "High Speed Sync" and Nikon refers to it as "Auto FP High-Speed Sync." This leads to two questions:

- Can your camera/flash combo shoot in high speed sync?

- How do you turn this feature on?

What about your camera and flash ? Here are some options.

Canon "High Speed Sync"

- Compatible flashes: 580EX, 550EX, 430EX, 420EX

- Compatible cameras: EOS-1 series film and digital, EOS-5D, EOS 30D, EOS 20D, EOS 10D, Digital Rebel XT, EOS-3 (refer to manual for older bodies)

Canon's High Speed Sync is turned on from the flash. On the 580EX there is a single button on the back of the flash which cycles among Standard, High-Speed Sync, and Second Curtain Sync.

Canon Speedlite 580EX

A single button cycles among standard, High Speed, and Second Curtain sync. A lightning bolt-"H" icon appears when High Speed Sync is enabled.

On the 550EX there are two adjacent buttons that you press simultaneously. If either flash is attached to an older EOS model that's not capable of High Speed Sync, you won't be able to set this mode on the flash.

Canon Speedlite 550EX

Two buttons must be pressed simultaneously to cycle among standard, High Speed, and Second Curtain sync.

(I leave High Speed Sync enabled on my Canon flashes. Be aware that if you remove the flash batteries for more than a few minutes, this setting will default back to standard sync. I've been burned by this more than once.)

Nothing needs to be set on Canon bodies. In the viewfinder, a small "H" will appear next to the flash lightning bolt icon when this feature is turned on and the shutter speed exceeds the maximum sync speed. If you turn High Speed Sync off on the flash, you won't be able to set a shutter speed higher than the sync speed. The shutter speed will flash to warn you if this results in overexposure (e.g., in Aperture Priority mode).

EOS 1D Mark II viewfinder display showing High Speed Sync is on.

Nikon "Auto FP High-Speed Sync"

- Compatible flashes: SB-800 and SB-600 (refer to manual for older flashes)

- Compatible cameras: D2X, D200, D2Hs, F6, F5, F100

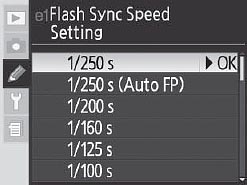

Nikon users can enable Auto FP High-Speed Sync on the D2x and D200 with Custom Setting e1: Flash Sync Speed Setting on certain Nikon cameras. Set this to 1/250 sec (Auto FP). (Refer to the manuals for other bodies.)

Nikon D2x Menu

Set Custom Setting e1 to 1/250 s (Auto FP) to enable High Sync mode.

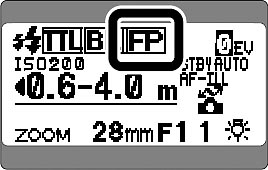

Nothing needs to be set on the SB-800 and SB-600 flash. These flashes will show "FP" on the display when the feature is enabled on the camera.

Nikon SB-800 flash

The flash panel will display "FP" when Auto FP High Speed Sync is set on the camera.

Other camera systems

Canon and Nikon aren't the only manufacturers to offer some form of high speed flash sync. Check your camera and flash manuals for other brands.

High speed flash sync is so useful to me that I won't buy a camera/flash combo that doesn't offer it.

I will point out that high speed flash sync is so useful to me that I won't buy a camera/flash combo that doesn't offer it. If you want to use fill flash with wildlife, people, or sports shooting, especially with long lenses, be sure to insist on this feature.

4. Shooting with High Speed Sync

In both Nikon and Canon systems, the flash reverts to "standard" mode whenever the shutter speed drops down to the maximum sync speed or below, so you can keep this feature turned on and it will kick in whenever the shutter speed exceeds the sync speed. I leave this feature on all the time for my normal shooting (there are some "advanced" flash tricks where you need to turn it off).

With high speed sync enabled, you're free to use flash at any shutter speed. This is a great advantage with telephoto lenses, or any time you want a high shutter speed, or a wide-open aperture that requires a high shutter speed for proper ambient exposure (e.g. for selective focus and blurred backgrounds).

How it works

Recall that in "standard" flash mode, the flash output is a very brief pulse, usually much shorter than the shutter speed. As flash engineers worked on ways to produce ever-faster stroboscope flash modes (many pulses per second for stop motion sequences or disco dancing), they realized they could pulse the flash thousands of times per second to produce an essentially continuous beam of light (for brief periods).

So in high speed sync mode, the flash fires continuously, many thousands of times per second. All these pulses of light essentially merge together into one long "pulse" that stays on the entire time the shutter is open. This is a lot of work for the flash to do; but it only has to do it for very short periods of time (i.e., less than the standard sync speed, such as 1/200 sec or less).

So in high speed sync mode, the flash stays "on" for the entire time that the shutter is traveling across the frame. There's no longer a problem with parts of the frame blacking out behind the shutter curtains as they sweep across the frame. Now you can use fill flash at shutter speeds of 1/8,000 second!

Limitations (the fine print)

The first limitation to be aware of is that you lose about one stop of flash power when you switch to high speed sync. This is usually a small price to pay for the advantages of high shutter speed and/or wide-open aperture.

In addition, if you look at the output power charts in the flash manual, you'll see that for every stop increase in shutter speed, you lose another stop of flash power. Some people incorrectly conclude from this that the flash output is so small at high shutter speeds that it must be useless. That's a mistake.

This power loss isn't as bad as it might first seem.

This power loss isn't as bad as it might seem. Keep in mind that because you're also opening up then lens one f/stop for every stop that you increase the shutter speed (to keep the same ambient exposure), you're essentially getting back that "lost" flash power. So you've only lost the initial one stop output decrease that kicks in when you first switch to high speed sync mode.

Note that for Canon and Nikon, you can leave high speed sync "on" all the time, and it will only "kick in" when it is needed. At shutter speeds at or below the sync speed, the flash operates in the "standard" mode, and there's no power loss. I recommend leaving high speed sync enabled all the time, unless you're doing something advanced with your flash where you know you don't want it (like hummingbird photography, or using your hotshoe flash to trigger studio strobes).

Another consideration is that you're losing the motion stopping ability of standard flash when you switch to high speed sync. This happens because, instead of the ultra-fast pulse of flash light you get in standard mode (1/1,000 to 1/50,000 sec depending on subject distance), you're now leaving the flash on for the entire exposure. (This is a consideration for one of my specialties, hummingbird stop-action photography.)

Of course, high speed sync is only kicking in at relatively high shutter speeds, higher than the standard sync speed, so some motion will be stopped anyway by the high shutter speed. This is a consideration if you're using the creative effect of "flash ghosting," where a moving subject is blurred in the ambient exposure, but a frozen image is superimposed on this by the ultra-fast flash pulse in standard (non-high speed) mode. You can't get ghosting in high speed sync mode. If your shutter speed drops below the sync speed, however, the flash reverts to standard mode and this effect will return.

What about Second (Rear) Curtain Sync?

A final question people sometimes have is, "Why can't High Speed Sync and Second Curtain (Rear Curtain) Sync be used at the same time?" Second curtain sync is used for creative flash photography with moving subjects and long exposures. It's key feature is that the flash doesn't fire until the end of a long exposure (in normal mode the flash fires at the beginning).

A second curtain sync image of a person walking will show a frozen-motion flash image combined with a "trailing" blur behind the moving subject, conveying a sense of motion in your image. In normal or first curtain sync, the blur would be "in front" of the person, who would then appear to be walking backward.

However, if you review what I've told you about how all these flash modes work, you'll realize that High Speed Sync and Second Curtain Sync are mutually exclusive—you can't do both at the same time. I'll leave that as an exercise for you to consider.

Recap

Canon's High Speed Sync, Nikon's Auto FP High Speed Sync, and similar technologies now allow you to use flash at any shutter speed, effectively doing away with the old limit of maximum sync speed. Both camera and flash must offer this feature. Without it, your flash will force your camera to a shutter speed no faster than its maximum sync speed, which in turn will require you to use smaller apertures.

For action shots of people or wildlife, outdoor portraits with wide apertures and soft backgrounds, or long lens shooting in general, high speed sync will overcome the old limits of flash sync speed, and let you use flash at any shutter speed. It's a great tool in the flash photographer's arsenal. Look for it when you buy—and be sure you know how to turn it on.

Green-crowned Brilliant, Costa Rica

EOS 1D Mark II, ISO 400, 500 mm lens + 1.4X, 1/350 sec @ f/5.7, fill flash @ -1 with Better Beamer Flash Extender and Speedlite 580EX in High Speed Sync mode. Fill flash helps bring out the incredible iridescence of this tiny hummingbird.